The gift is to the giver, and comes back most to him–it cannot fail… – Walt Whitman

The gift is to the giver, and comes back most to him–it cannot fail… – Walt Whitman

I’ve been reading the modern classic The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World by Lewis Hyde, a book I ordered upon seeing how much Seth Godin referenced it in his book The Icarus Agenda.

Hyde explores the economics of human gift giving. Why is the concept of the gift something so important in all human cultures? And what does it mean to make a gift or your art…and why would/should you? (The only tragedy about this book is the way it’s marketed on its cover blurb: “…cherished by artists, writers, musicians, and thinkers.” One of the main thrusts of Godin’s aforementioned Icarus Agenda is that all work is art (or can be). So marketers, SEOs, web developers…all should be artists creating art. And so The Gift is relevant to them as well.)

Gifts in Motion

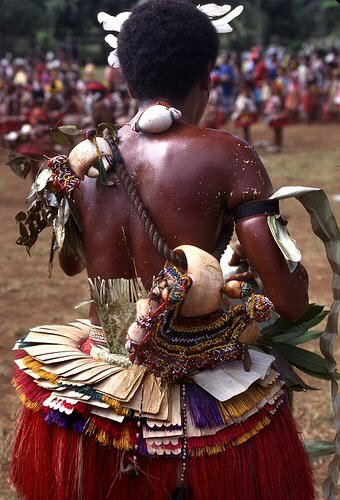

Early in the book, Hyde introduces us to the Kula, a ceremonial, never-ending gift exchange practiced by the people of the Massim archipelago off New Guinea. There are two kinds of gifts, armshells (a shell ring worn about the wrist) and shell necklaces. These gifts are exchanged around the archipelago in a circular motion; one going clockwise and the other counterclockwise. Anyone receiving one gift is expected to reciprocate with the equivalent value of the other kind within no more than a year. In this way, the gifts are continually in motion, travelling from island to island in a cycle that stretches from two to ten years for any one gift before it returns to its originator.

Hyde comments, “…at the level of each man there will be the sense of imbalance, of shifting weight, that always marks a gift exchange.” Take note of that: giving a gift creates a (temporary) imbalance. The giver is without something, and the recipient has acquired a social obligation (to reciprocate and to move the gift along).

A strict ethic governs this gift exchange. First, it is considered very impolite to discuss the value of the gifts, and whether the reciprocal gift is really of equal value (even though everyone clearly knows that it should be). Second, there is no recourse or reprisal if the reciprocal gift turns out to be of lesser value. It is a gift, not a contract, and must be received as such.

When we barter we make deals, and if someone defaults we go after him, but the gift must be a gift. It is as if you give a part of your substance to your gift partner and then wait in silence until he gives you a part of his. You put your self in his hands. These rules–and they are typical of gift institutions–preserve the sense of motion despite the exchange involved (p. 19).

So the important thing is the motion, and the motion is fueled by temporary loss of equilibrium.

I remember as a boy reading a book on how to animate cartoon characters. In a discussion on animating a running man, the author commented that the process of running starts with a falling forward. A human preparing to run actually leans forward, intentionally (though not consciously) throwing off his balance, which is corrected by putting the first foot forward–as step. The runner in motion is someone continually falling forward. The lean is the loss of equilibrium; the step is the “gift” that restores it.

When we think of an exchange of gifts in the West, our minds tend to go first to two-way reciprocal giving. Christmas cards are an example of this. When I was growing up, we kept a list of the people who had sent us cards the year before to be sure we sent them a card the next year. But if we didn’t get a card from someone for a year or two, they were crossed off our list.

But the Kula is non-linear and therefore not really reciprocal. It requires at least three parties (in reality, of course, many more are involved), and the same gift doesn’t immediately return to the giver. Hyde points out that most folk tales involving gifts have at least three people in them, establishing the minimum for a circle. The circle helps perpetuate dis-equilibrium and motion. No one ever receives the same gift from the same person. I may give armshells to my neighbor to the west, but I will never get armshells back from him. I have to give “blindly” and have “blind gratitude” as well. The gift “goes around a corner” as it were, before it comes back, and I usually will be unaware of all the connections it went through before it does return. When a gift has passed out of sight, it can’t be manipulated by the giver.

The Professional Giver & the Circle of Life

So what does all this mean for the marketing professional, the knowledge worker, the purveyor of expertise?

What we sell each day is very akin to art. For the most part it is not a commodity that our customers can purchase off the shelf, to place on their own shelves. We could treat it completely as Kula, a gift to be given without barter and without expectation of direct reciprocation. And some do. For example, retired business executives who volunteer to mentor young entrepreneurs. Or we could treat it strictly as capital, hide it all behind a paywall, and only dole it out to paying customers.

If we choose the former, we will be forced to do something else to put food on our tables, and thus rob time away from becoming better experts in our field. (The knowledge professional’s most precious “commodity” is her time for self-education and experience-building.) If we choose the latter, we miss out on all that the Gift Circle could do; we short circuit humanity, even if only in a small way.

Kula gifts – Photo from oneworldpool.blogspot.com

Perhaps the people of Massim show us a third way.

The Massim have both Kula (the ceremonial gifts) and barter. The two exist in the ebb and flow of their lives, and they don’t confuse them. Both are valued. There is a recognition that some things need to be kept long term and some things consumed in order to survive. These things are either made or bartered for. But there is equal importance given to the gifts, for they bind the tribe. Their motion between the islands is the blood pumping through the Massim arteries that keeps the tribe alive and vital. Among other social functions, it provides incentive to maintain contact between islands that may be hundreds of miles apart. No island can be fully self-sufficient, for there will always be times to move the Kula.

When experts do Kula, they keep the world moving and build tribes.

Kula is the recognition that what we have is a gift. Sure you worked hard to acquire the knowledge you have, but how much surrounding your ability to do that is pure gift? Did you create the intelligence you have? Did you choose the family into which you were born that provided you with certain opportunities to grow and to learn? When so much has come to you from one island, shouldn’t you pass some of it on to the next?

And by sharing the Kula, you build a tribe that you are a part of. Far off peoples will benefit from you around the blind corner of the giving, and the whole tribe gets better because of it. And that means you get better too, for you are part of the tribe.

Giving by sharing your expertise freely when possible (especially for those who could never afford to pay you back for it) is a kind of “falling forward,” like the animated runner we mentioned earlier. It throws off you equilibrium in a positive way, keeping you just enough off balance that you must continue to learn and grow.

What do you think? Is the concept of Kula applicable to 21st century Western business? Do you offer up your expertise sometimes as a gift with no immediate expectation of return? If so, why do you do it?

Here is a Haiku Deck visual version of this blog post:

Created with Haiku Deck, the free presentation app for iPad

******

By the way…Tim Rayner (Twitter | Google+) has begun an excellent series on Social Media As a Gift Culture which is going much more in depth into Lewis Hyde’s book and examining how social media could create a Western-world gift culture. Highly recommended! (The link goes to part two, which has a link early on to part one.)

My answer is: I sure as hell hope so. I do feel that I see a bit of this going on in our community already. Could it possibly be only the people that I have chosen to interact with? Maybe.

What I can tell you is that I sat in a cafe on a snowy Saturday with two people that were at square one. They had no idea where to start and no idea how to connect the dots. I only planned to sit with them for an hour and a half. I ended up spending 3 hours with them, explaining ideas, concepts and strategies. Why? Because you, Phil and Martin have done the same for me and when I realized that this, right here was a situation to pay it forward, give back or just gift the knowledge that was given to me to someone else, I was overjoyed at the opportunity!

I pass along my knowledge because it makes me happy to help people.

And THAT is worth more to me than any paycheck I receive. To hear that the gift went around the corner. It landed on another island. And what I and a few others might do keeps expanding like ripples in a pond.

I like the concept of giving more than was expected. Godin talks about this a bit. When you get paid for a job that both sides feel that everything is even and squared away – a day’s pay for a day’s work.

But the “gift” part comes when you give more that was asked. You get paid a days wage, but you have given more of yourself. You’ve given something that can’t really be repaid. When you inspire someone, or delight a customer it’s impossible to put a price on that.

I totally agree and I’ve also noticed that sharing more with a client really creates a deeper relationship, beyond business sometimes. I also see it as my own success because the ultimate goal as a consultant is to have my clients succeed.